Never File a Continuation-in-Part

By Ed Ryan

While Continuations and Divisionals are common, Continuations-in-Part (CIPs) are an oft-forgotten, oft-misunderstood third option for continuing a patent family. Mixing features of Continuations and new filings, they present a temptation to practitioners who feel trapped by an inadequate disclosure and to inventors who have continued developing their invention after filing. However, CIPs have little to offer beyond what can be had in a new filing and many misunderstand the implications of the CIP’s multiple priority dates, leading to surprising problems.

What is a CIP?

A CIP is halfway between a continuing application and a wholly new application. It inherits the priority date of its parent application for all material in the original disclosure, but allows the inclusion of new matter with a new priority date attached to it. The general terms of a CIP’s filing and use can be found in MPEP 201.08.

In most ways, the filing of a CIP resembles that of a Continuation or Divisional, but may include additional description and figures, providing entirely new embodiments that were not included in the parent application. Furthermore, a CIP can include material that elaborates on the original disclosure, for example including experimental results or implementation details that were originally unavailable.

The key to understanding CIPs lies in the priority dates. While many practitioners believe that CIP claims are treated element-by-element to determine respective priority dates, in fact a claim can have only one priority date. As MPEP 211.05(I)(B) says, “Only the claims of the continuation-in-part application that are disclosed in the manner provided by 35 U.S.C. 112(a) in the prior-filed application are entitled to the benefit of the filing date of the prior-filed application.” Thus, a claim that includes any material that is not supported by the written description of the parent application will have a priority date that is determined by the filing date of the CIP. See Id.

What happens when you file a CIP with mixed claims?

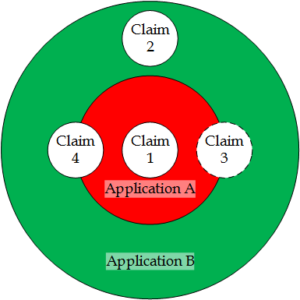

Consider an example CIP Application B, filed during the pendency of parent Application A. Application B discloses everything from Application A, but adds new material as well. Application B includes the following claims:

- Claim 1 is fully supported by the disclosure of Application A.

- Claim 2 is supported solely by material introduced in Application B.

- Claim 3 is described by the disclosure of Application A, but enabled by material introduced in Application B.

- Claim 4 is partially supported by the disclosure of Application A and partially by material introduced in Application B.

Claim 1 is entitled to the benefit of Application A’s earlier priority date, while claim 2 is clearly limited to the filing date of Application B. While the treatment of claims 1 and 2 is straightforward, the examples of claims 3 and 4 are frequently misunderstood.

For claim 3, practitioners may want to cure an enablement problem or other formal deficiency by filing a CIP that introduces the enabling disclosure. However, as MPEP 201.08 makes clear, only claims “that are disclosed in the manner provided by 35 U.S.C. 112(a)” are entitled to the earlier priority date, and the written description, enablement, and best mode requirements derive from §112(a). Thus, if the claims are not fully supported by the original filing, then their features are not disclosed in the manner provided by 35 U.S.C. §112(a). Claim 3 is not entitled to the earlier priority date.

For claim 4, a practitioner may, for example, want to introduce new material to overcome an Alice rejection in an application that was filed before the Supreme Court decision. The claims would thus recite the original invention, plus features calculated to overcome a rejection based on 35 U.S.C. §101. However, because the new features were not supported by the original disclosure, they are not entitled to the earlier priority date. There is no element-by-element consideration of priority date, and claim 4 is not entitled to the earlier priority date.

The consequences of priority date confusion

The most obvious consequence of a claim having new features is that intervening prior art may be used to reject the claims–any reference filed between Applications A and B would become valid prior art. What practitioners often fail to realize, however, is that the parent application may also be used as prior art against those claims.

The only thing that preserves Continuations and Divisionals from this fate is that they share the priority date of the parent application. When that benefit is unavailable, the parent application is treated like any other reference under 35 U.S.C. §102(a)(1). The CIP is naturally still safe under 35 U.S.C. §102(a)(2), as long as it lists the same inventors as the parent, and the exceptions of §102(b) still pertain. The result is that the applicant has two and a half years (one year after the parent application’s publication) to file a CIP, before the parent application itself becomes prior art. If the CIP is filed after that point, otherwise patentable features that derive from the parent disclosure may be inadvertently lost.

Providing enablement

The situation is less dire when the CIP is filed to address an enablement rejection. As MPEP §2121.01(I) states, “Where a reference appears to not be enabling on its face, however, an applicant may successfully challenge the cited prior art for lack of enablement by argument without supporting evidence.” Thus, if an enablement rejection is on the record in the parent case, that should be enough to establish in a CIP that the parent application cannot be used as a prior art reference.

But claims are only entitled to the benefit of the parent’s priority when the parent application discloses every feature in those claims in compliance with §112(a). While the parent application would not qualify as prior art, intervening references would still have full effect in this scenario, even if the claims find written support in the parent specification.

A CIP provides few benefits over a new application

When it comes to the prior art then, filing a CIP is no better–and no worse–than filing a new application. But even under the best of circumstances, with no intervening prior art, the CIP will have a shortened term due to inheriting the parent’s earliest filing date and will still inherit any prosecution history estoppel incurred during prosecution of the parent. As a result, it is difficult to justify filing a CIP under any circumstances.

Comment (1)

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nam viverra euismod odio, gravida pellentesque urna varius vitae, gravida pellentesque urna varius vitae.

Comments are closed.